Saturday, April 26, 2008

Ethnic Literature: A Criticism

I find Reilly interesting because it is one of the few essays I've read that isn't afraid to be critical of the ethnic literature genre. Certainly, there is a plethora of material that supports the study and writing of ethnic literature, such as Achebe or Ngugi, to name a few. While I don't know that I necessarily agree with everything that Reilly has to write, he raises interesting questions about what defines certain genres of literature. In particular, he points out typical "scheme" that serves as a map for the writing of ethnic literature, which, in Reilly's view, makes ethnic literature easier to interpret.

While I am intrigued by Reilly's criticisms of ethnic literature, it seems dangerous and ignorant to declare that all ethnic literature fits into a particular, unoriginal pattern. He neglects to recognize works that have stood out in the field of ethnic literature, or work that has stirred up the field of ethnic literature, and he limits his discussion to ethnic literature within the American landscape. Ultimately, however, I feel like it was important for me to read this essay, if only for the exposure it gave me to an alternative point of view when it comes to ethnic literature.

In response to "On Reading Ethnic Literature Now"

Thursday, April 24, 2008

On the necessity (or not) of the English Department

Ngugi et al. make an compelling case for their argument. They write that the "primary duty of any literature department is to illuminate the spirit animating a people, to show it meets new challenges, and to investigate possible areas of development and involvement." In offering a number of different courses that reflect the African composition, the University of Nairobi would encourage an appreciation for the history of African literature and culture. Their essay convincingly argues for a curriculum not based on European literature, which has so often been the norm for literary studies, but instead, for a curriculum that focuses on their own history and culture.

After reading the essay, I wondered what this type of literary curriculum would look like for literature departments in the United States. The English department at Messiah undoubtedly focuses primarily on English literature, with a number of my courses teaching such British authors as Shakespeare, Keats, Hardy, Donne, etc. While the United States was colonized primarily by English settlers, it would be inaccurate to say that our culture is predominantly English-based. The United States prides itself on being a melting pot, a country where different cultures live together to form a unique, cohesive culture, and yet our literature departments don't reflect our own cultural composition.

During my sophomore year of college, I took an ethnic literature course in which I read books that reflected a number of different cultural backgrounds. While the course was a literature course, it was not a part of the English department curriculum. And while I am grateful for everything I've learned in my English classes, including the various English literature courses I've had to take, there definitely seems to be some sort of disconnect between writing and literature departments and the various cultures in the United States.

It's strange for me to say that even as an English major, I wouldn't be opposed to the abolition of the "English" department at Messiah College. To call a literature/writing department an English department is to put limits on what can be taught, or what can be understand to be of any worth in the literary canon. So while I am a great advocate for the study of literature and writing, I am also an advocate for the abolition of the "English" department.

Saturday, April 19, 2008

On the Issue of Otherness

Of the issues raised in the essay, I found the concept of otherness to be the most intriguing. John Lye, the professor who wrote the essay, asserts that post-colonial theory is "built in large part around the concept of otherness," an issue that raises such compex questions as whether or not the concept of otherness reduces numerous cultures to a single identity, as well as whether this concept of otherness portrays the Western world as orderly and rational, while the "oriental" world (to borrow Lye's term) is chaotic and irrational. In addition, Lye questions whether the use of the term otherness attempts to reclaim a fragmented past, an activity which is, in Lye's view, futile.

I found Lye's essay to be compelling for a number of reasons. As I've mentioned in a previous post, I think it's difficult to boil down issues like colonization and race into a neat package through which we can examine other texts. It's dangerous to put anything in black and white terms, especially ethnicity and issues of post-colonization. This concept of otherness, which Lye feels is so central to the argument of post-colonial criticism, is particularly difficult to deal with because it forces a number of different cultures and ethnic identities to be placed under one label. I think that it's important to respect the various identities of those who have been under colonial rule, and that includes avoiding broad labels to define post-colonial critics.

Post-colonial criticism is particularly interesting to me because of all the complexities that make up the term. Who or what writing is considered post-colonial? What does post-colonization look like in literature, or in criticism? Is it wrong to view texts through a post-colonial critical lens?

I don't claim to have all the answers, and I'm okay with that. I don't know that it's possible to ever arrive at a definitive conclusion for such complex issues, but I will continue to enjoy being challenged by such difficult concepts as otherness, whatever otherness actually means.

Problems with Post-colonialism

What's wrong with the term post-colonial lit?

For some post-colonial critics, using the term "post-colonial" to describe anything leads a writer or critic into murky waters. What authors can be included in the post-colonial canon? Is looking at literature through a post-colonial lens Eurocentric, for it limits the significance of a nation to the time it was colonized?

In a paper posted on the Washington State University website, Paul Brians addresses the controversy surrounding the use of the term "post-colonial," arguing that "more it is examined, the more the postcolonial sphere crumbles. Though Jamaican, Nigerian, and Indian writers have much to say to each other; it is not clear that they should be lumped together." Brians does, however, admit that until a better term comes along, it's difficult to avoid the "post-colonial" tag when discussing literature that deals with the culture identity of formerly colonized nations.

All of this leads me to wonder - is post-colonialism a legitimate form of literary criticism? Certainly, the literary community must have the discussions that arise from questions post-colonial critics put forth. In the same way that Marxists for Feminists seek to examine texts through the minority perspectives, so too do the post-colonial critics.

While post-colonialism is undoubtedly a more controversial form of criticism than, say, Formalism, I tend to agree with Brians that until we can find better a better term or definition, we must continue to utilize the term "post-colonial criticism" in our studies, however reluctant we may in embracing that term. Objections can be raised to any form of literary criticism, and simply because post-colonial criticism might raise more questions is no reason to ignore the field altogether. We may be uncomfortable with the direction that post-colonialism takes us, but it doesn't make the journey any less vital to our own literary understanding.

Post-colonialism Through Achebe's Eyes

As I began to engage with the critical essays on Ethnicity and Post-colonialism, I decided to revisit an essay I'd read in the past, Chinua Achebe's "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness." I first encountered this essay after reading Heart of Darkness for a Post-colonial literature class, and at the time, I really struggled with how to deal with some of the ideas that Achebe puts forth.

Issues like post-colonialism can be highly sensitive, and it can be hard, for me at least, to be critical of Achebe's essay. While I don't agree with everything Achebe has to say in this essay, at the same time, I realize that my own world view is very limited, and I can never fully understand or empathize with Achebe's perspective. What I found especially hard to understand about Achebe's essay was how we all could have had it so spectacularly wrong about Heart of Darkness.

Even before I first read Heart of Darkness, I had long heard the praise for the way the novella portrayed with unflinching clarity the brutality inflicted upon the people of Africa by European settlers. After I had read Conrad's work, I viewed the story in much the same way as the critics who had praised it, admiring the way Conrad showed the evils of the European settlers, and in particular, the terrible savagery of Kurtz.

I read Achebe immediately after I first read Conrad, and the essay raised some poignant questions for me about the way Heart of Darkness portrayed Africans. Did we view them as just metaphorical tools to act as a foil for Conrad's alter ego, Marlow? Was it really the Africans portrayed as savages, not the Europeans like Kurtz?

The complexity of my current beliefs on Heart of Darkness prevent me from succinctly articulately them here, but in short, though I still don't endorse all the beliefs that Achebe puts forth, I appreciate the way Achebe has opened my mind up to alternative views. It was only after reading Achebe's essay that I first began to realize the importance of viewing texts through a different lens, examining the way different groups might approach the text in a way that is in stark contrast to my own approach.

Though controversial, Achebe is, in my opinion, a good place for one to begin their post-colonial studies. He does what the best critics do, in that he raises questions for his readers and provides an alternative viewpoint through which we may examine familiar texts.

Saturday, April 12, 2008

Woman Must Write Woman.

For Helene Cixous, the answer to both seems to be yes. Cixous writes like a general rallying her troops for battle, urging women to write for women, as women. "I write woman: woman must write woman. And man, man" she writes, rallying women to not only be readers, but writers of literature, a literature written as woman literature.

It's hard for me, as a female English major, to not be a bit moved by the words of Cixous. She is at once rational and irrational, proud, angry, and inspiring. She nails some things on the head - in particular, I really resonated with her section on why women don't write. Though I am an English major and by extension, a writer who writes not in secret but for assignment, openly and often, I have experienced much of what Cixous discusses. Did I feel my writing wasn't good? Of course. Is writing too great for me? Yes, probably. Have I written in secret before? Often enough.

What makes Cixous intriguing, then, is the way she stirs the woman writer out of this secrecy, shoving inhibition aside in favor of finding a female voice, a voice that will not, in Cixous' view, be hampered or determined by man, but will speak in spite of man. She writes, "Men have committed the greatest crime against women. Insidiously, violently, they have led them to have women, to be their own enemies, to mobilize their immense strength against themselves, to be the executants of their virile needs." While I don't know that I would necessarily agree that men have caused me to hate women, I would argue in Cixous' favor that the oppression of women by men for centuries has resulted in women, and women writers especially, viewing themselves as less than they are.

Though I don't want to pursue writing after graduation, I found myself surprisingly inspired by the work of Cixous. Why shouldn't women write for woman, as woman? Going further, do we have an obligation to write for woman, as woman? While I don't think that female writers are obligated to write in any fashion, I do think it's important to female writers to be fearlessly independent, not imitating the work of men, but instead, forging out on their own as the intelligent, powerful writers they are capable of being.

Thursday, April 10, 2008

Binary Oppositions

In a class assignment that put lists of binary oppositions into two distinct columns, I was surprised to see the varied results that arose from each of the groups in class. What I found most interesting, however, was the way that we related the binary opposition of man/woman into our previously developed list.

In our list of binary oppositions, we related the words premeditated, traditional, success, urban, light, and parent to man. The counterparts we related to woman included spontaneous, unorthodox, failure, rural, dark, and child. I found it interesting that we associated words that conveyed a sense of strength and stability with man, while we grouped woman with words that seemed to convey a sense of instability. Our associations made me recall The Madwoman in the Attic, a text that argues the "madness" of women as a metaphor for their repressed anger.

In response to our lists, I wondered if societal beliefs were to account for our associations. Why do I relate words such as strength and parent with men? Did I really believe that men are stronger and more stable than women? While I don't think that I necessarily believe men to be more successful or stable than females, I do believe that there is some sort of societal construct that sends that message.

What I found really interesting about the binary oppositions and the lists produced as a result of our associations was the way our class produced different associations for man/woman. Certainly Structuralists would argue the differences in our class lists are purely incidental, and to some extent, I would agree that these varying associations seem to be purely incidental. Media and society send very strong messages about male and female roles, and I think that our perceived notion of men as more successful, established, and stable is probably a universally accepted notion, whether or not it's correct.

I find the whole notion of binary oppositions to be interesting, and I'm especially interested in the discussions that develop as a result of these oppositions. It seems that in the case of our class exercise, binary opposition lists do indeed reflect some inner beliefs, whether these beliefs are held true or not.

Saturday, April 5, 2008

The Androgyny of Virginia Woolf

In her article “Virginia Woolf and Androgyny,” author Marilyn Farwell explores the issue of what it Woolf is getting at in her use of the term “androgyny” in feminist criticism. Farwell writes that one of the issues complicating the matter of Woolf's use of androgyny is the myriad of definitions critics have used to describe Woolf's criticism. Proposed definitions of Woolf's androgyny have encompassed everything from the balance between “the poles of intuition and reason, subjectivity and objectivity, anima and animus, heterosexuality and homosexuality, and finally manic and depressive.” Farwell's list intrigued me, for I had really only considered sexual androgyny, in terms of the different sensibilities of men and women, to be the meaning of the word Woolf used in her critical examination, “A Room of One's Own.”

For Farwell, however, androgyny as used by Woolf is either a fusion of distinct elements or the interplay between two disparate ideas, and the differences between these two definitions are, in Farwell's opinion, crucial to the understanding of Woolf's criticism. In avoiding a definitive use of androgyny, Woolf creates an ambiguous term that has continued to intrigue critics. Despite Woolf's own perceived ambivalence in defining the term, however, Farwell defines the androgyny of a writer as a “width of perception rather than by a single, universal mode of knowing.”

I find Farwell's definition of the term androgyny to be an intriguing one, particularly in light of Woolf's own writing abilities. The idea of androgyny as spanning the width of two disparate ideas, rather than a joining of the two, represents Woolf's own musings on the straightforward nature of a man's writing vs. the indirect writing of females. Woolf's androgyny, then, would seem to be the ability to be both indirect and straightforward, whatever that may look like.

All of this leads me to wonder if this sense of androgyny is needed in successful writing. Must one be able to span two disparate ideas or thoughts skillfully to achieve significant, important art? Though I don't believe I have yet discerned this answer myself, I'm intrigued by this idea of androgyny as something that spans ideas rather than joining them. Androgyny seems to offer a greater intellectual freedom, and perhaps this is what Woolf strove for after all.

The Intellectual Distinction

In his book Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, Pierre Bourdieu makes a compelling argument that suggests that in fact, the social conditions we have been raised in are intrinsically linked to our understanding of culture and art. Bourdieu writes, "Whereas the ideology of charisma regards taste in legitimate culture as a gift of nature, scientific observation shows that cultural needs are the product of upbringing and education . . . preferences in literature, painting or music, are closely linked to educational level, and secondarily to social origin." For Bourdieu, the culture in which we are raised does not solely impact our cultural appreciation, but instead, determines our cultural appreciation.

Bourdieu's idea is an interesting one. I've long been interested in what determines one's appreciation of art, music, and literature, and have strove in vain to understand why certain works have been praised by the cultural elite, while other works are frowned upon. I'm reminded of my immediate reaction to Henri Matisse's painting The Snail (at right), a painting which has been fairly universally praised by art critics and, I'm told, exemplifies Matisse's understanding of color in his work. While I appreciate that others can appreciate and enjoy the painting, I confess that I'm at a loss to understand the significance of the work. To me, it looks like something I could have done in my elementary school art classes, and I'm no Matisse.

This brings me back to Bourdieu. In his book on this so-called "intellectual distinction" he writes, "A work of art has meaning and interest only for someone who possesses the cultural competence, that is, the code, into which it is encoded. " Is it possible that I do not possess the cultural code needed to understanding the significance and meaning of Matisse's The Snail? The theory is an intriguing one. Certainly, I agree with Bourdieu's assertion that no person is autonomous in their understanding and appreciation of art and culture, but I must also admit that I question the totality of his argument.

I wonder how Bourdieu would respond to the dissimilarities in cultural appreciation even among those with similar cultural backgrounds. In my time at Messiah, I've come across those who have a very similar background to my own, in terms of cultural exposure and education, yet still cannot understand why the novels of Ian McEwan are so powerful or how significant the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins is to English literature. I'm often told by friends who are not in the English department that they just don't get poetry, and no matter how hard I might try to dissuade them of their initial impressions, nothing ever seems to change.

Similarly, my siblings and I tend to appreciate different types of art, despite our identical upbringing. I tend to favor Impressionist works, while my brother is able to discern the significance of current artists like Damien Hirst and Banksy. While I tend to agree with much of Burdieu's argument, I believe he fails to account for these distinctions in cultural appreciation, which perhaps, do act as evidence for the belief in cultural autonomy.

Friday, April 4, 2008

Direct and Straightforward

Is the writing of men more direct and straightforward than the writing of women?

After reading Virginia Woolf's essay "A Room of One's Own," one would be inclined to think so. Indeed, even Woolf's own writing would seem to support her assertion that the writing of men is "so direct, so straightforward after the writing of women."I read Woolf's novel To the Lighthouse a few years ago for one of my English literature classes, and certainly, her meandering, difficult to follow narrative can be trying on one's patience when reading. Woolf, as a female novelist, seems to be the antithesis of her description of men's writing. She isn't direct or straightforward, preferring to remain free, introspective, and discursive.

All of this leads me to wonder - what is so wonderful about being straightforward? While I fully admit that part of my reaction to Woolf's assertions may be an immediate need to defend female novelists, at the same time, I do occasionally appreciate and enjoy that which is not direct or straightforward. I loved To the Lighthouse, fully relishing in the ability to lose myself in the intricacies of the plot. Losing oneself in a novel is almost like solving a puzzle or mystery, in that you must be fully engaged with the text, looking for clues and paying attention to the minutest of details, to be rewarded. It is reading at its highest level, for it is reading that requires the reader to be a willing participant in introspection and stream of consciousness, journeying with the author through the narrative. It seems to me that many times, the importance of being straightforward is exaggerated or falsely elevated.

I am also shy to be fully in agreement with Woolf's assertions for the simple reason that I am reluctant to throw blanket statements on any group. Are all male novelists direct and straightforward? Certainly not. I think of novelists like James Joyce or William Faulkner who, like Woolf, are neither direct nor straightforward, and I see the error in Woolf's bold declarations on male and female writing.

In her essay, Woolf goes on to write that a certain man's writing "indicated such freedom of mind, such liberty of person, such confidence in himself. One had a sense of physical well-being in the presence of this well-nourished, well-educated, free mind, which had never been thwarted or opposed, but had had full liberty from birth to stretch itself in whatever way it liked." After my previous reflections on the benefits of directness in writing, I must wonder why, in Woolf's view, straightforward writing is synonymous with confidence and freedom. Indeed, it seems to me that to be indirect, to write without being straightforward or explicit, requires more confidence. You must trust the reader to be patient with you, confident in your abilities to create an intricate, meandering plot and relishing in your freedom as a writer. Yes, I would assert that Woolf's descriptions befit writing that is not straightforward.

Ultimately, while I appreciate Woolf's comments regarding male and female diversity in writing, I find myself wholly disagreeing with them. I delight in the intricate, taking pleasure in the male and female novelists that I continue to enjoy for their willingness to meander and be discursive.

Direct and straightforward? Both overrated.

Saturday, March 29, 2008

On Marxist Criticism

As someone interested in the field of publishing, I found the figures presented in Richard Ohmann's article "The Shaping of a Canon: U.S. Fiction, 1960-1975" to be revealing. On page 1884 of the text, Ohmann lists the number of ads vs. the page of reviews from the big publishing houses. The numbers were not surprising. Publishing giants like Random House and Little, Brown had the highest number of advertisements and the highest number of reviews, while smaller houses had considerably smaller numbers in both topics. Though the article was published years ago, I believe Ohmann's point is still valid.

Certainly, these numbers reflect scary facts for Marxist critics. Marxist criticism attempts to challenge the system of power in society, while the world of publishing seems to play into the idealogies of the bourgeoisie. In this way, the dominant "class" in publishing (groups such as Random House, for example) oppresses the lower "classes" in publishing, such as Ohmann's listed houses of Dutton, Lippincourt, and Harvard.

The issues of economic and political power have always interested, and yet I've rarely, if ever, applied these subjects to my literary encounters. After reading Ohmann's article and doing some independent research on Marxist criticism, I wonder how my readings of certain texts would be altered when approaching from a Marxist viewpoint. Whose story is being told in this text? What audience is being targeted by this text? All of these are vital questions when approaching a piece of literature as a Marxist critic.

More than the other views of literary criticism we've encountered so far this semester, I've found Marxist Criticism to be a compelling way to engage with literature. In examining literary texts through a different viewpoint and questioning the ideologies represented in the text, I may develop fuller and deeper understanding of a text. I find Marxist criticism to be an intriguing way to critique a text because it forces one to go beyond a selfish reading from one's own background and viewpoint to a reading that takes into account all economic groups and political ideologies.

Friday, March 28, 2008

What is a classic?

In many ways, I tend to agree that these characteristics are descriptive of classic literature. Certainly, classic literature seems to have some enduring qualities - if not, why would we continue to study the works of Chaucer or Shakespeare? There is a quality to classic literature that seems to continue to endure, allowing for these works to be appreciated for centuries.

But what is this quality of endurance? Do we continue to be that astounded by the language or storytelling ability of Shakespeare, or is it something more than that? I would venture to say that in many cases, the quality of universality has made classic literature endure. I think, for instance, that one of the reasons Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye has come to be considered a classic is the universal feelings of apathy, depression, and frustration we've all felt at some time. People continue to read it because people sometimes feel the same way Holden Caulfield feels.

Broad acclamation, however, is harder to easily define and describe. I can't say that I know what makes a piece of literature receive broad praise. The literature that really blows me away is that which tells an incredible story with amazing, descriptive language, teaching me lessons on not only how to be a superior storyteller, but how to use form and language to attain perfection in writing.

Of course, each of us has our own ideas on what makes a superior story. Or, we view the perfection of form and language in different ways, each of us looking for something different to learn from to perfect our own understanding about writing.

I find this notion of what makes classic literature to be classic an interesting one. Even with the few characteristics I've briefly fleshed out here, there seems to be a wealth of different opinion on this subject. And yet, the classics will endure, in spite of our not knowing why the work is truly a classic.

Saturday, March 8, 2008

The Death of the Author

In each of the schools of criticism we have examined this semester, I have been intrigued with the role of the author. While there were certainly great differences between Romanticism and the other criticisms we have studied in terms of their view of literature and reading, there does seem to be a consensus that the author is meaningless. I grant that on the surface the Romantics view of the author may seem strikingly different from that of the Structuralists or Formalists, but upon closer examination, I would argue that they may be similar than one may initially believe.

The Romantics believed that the author was a vessel of sorts, a channel between the spiritual and the human. In this way, the author is irrelevant to the overall success of the text - a piece of literature could be just as successful by a different "author." By the term author I mean another channel or agent in touch with the spiritual world of the origins of literature. This concept is an, in my opinion, an intriguing one. In the Romantics view, would the success of a piece of literature change were it interpreted by another agent? I believe they would say that it doesn't, so long as it accurately interprets or makes an impression of the spiritual.

In this way, the Romantics seem to have a similar view to authorship as the Structuralists or the Formalists. The author is pretty much irrelevant, and their intent is fairly meaningless. Literature is something beyond this human world, and the author is never as important as the spirituality of the text.

While I'm not sure that I have yet figured out my own view on the role of the author, I find the views of these critics intriguing, and in many ways, startling. It will be interesting to consider how my views might change as I engage with other forms of criticism throughout the rest of the semester.

What is Literature? Part 2

In my previous blog entry, I explored the issue of how to examine the Wiki novel in light of our frequent class discussions on what constitutes literature, what is reading, and what is an author. While I still don't have concrete conclusions on what the Wiki novel says about authorship, literature, and reading, I was still intrigued with the notion of online novels. With these questions still fresh in my mind, I examined another site for online literature, Hypertextopia.

Hypertextopia did a lot the work for me, devoting a whole page to defining literature. In Hypertextopia's view, defining literature is generally avoided because it leads to "false dichotomies" that separate any written word into literature and "not literature." Nevertheless, Hypertextopia attempts to define what they deem is worthy to be considered literature. They write,

If we accept the premise that literature is the highest expression of written language, then literature is characterized by a high density of meaning. Just as density is the amount of substance packed into a given space, the degree to which a work is literary is proportional to the amount of meaning packed into the words.

I find this definition to be intriguing, to say the least, especially in light of our class discussions on the significance of authorial intent when determining meaning. I'm sure that Wimsatt and Beardsley would argue that the meaning "packed into the words" is meaningless, and it's only significant what meaning is extracted from the words.

Ultimately, Hypertextopia defines literature as the body of work which is packed full of meaning. While I belive this definition certainly has some flaws, it's an intriguing way to begin examining what literature is, and more interestingly, what literature is in light of technology.

Tuesday, March 4, 2008

The Wiki novel: Literature or Not?

In our recent class discussions we've been focusing a lot on what constitutes literature, or authorship, or even reading, so needless to say, as I poked around the Wiki novel A Million Penguins yesterday, these questions repeatedly came up in my thoughts.

I found A Million Penguins to be fairly interesting, not just for the questions it raises about the nature of online social networking today, but also for the way it has in some ways manipulated what I have to come to define as literature. To my understanding, the Wiki novel was composed entirely of numerous different creative writing submissions, all compounded together to form a single cohesive "novel." In setting this project in motion, the creators of the Wiki novel sought to examine whether it is possible to create a solitary fictional voice from a collection of different writers, and in doing so, also examined what it literature, what is an author, and what is reading.

Truthfully, I didn't find the results of the Wiki novel to be that groundbreaking. While the premise of a combined novel is interesting, the end result of the work felt disjointed, and I didn't feel compelled to continue reading. These impressions made me consider what it is, then, to be an author, and whether or not a unified work must come from one author. In the case of A Million Penguins, it seems to be that in response to the question of whether a work must have a single author to be cohesive, the answer is a resounding yes.

When it comes to determining whether the Wiki novel can be considered a work of literature, my response isn't so emphatic. In the beginning, there seemed to be a storyline of sorts, which grew more and more convoluted with each passing chapter. Ultimately, there didn't seem to be a point to it all. It felt like 21 short stories with all the same character names, not one cohesive piece of literature. This led me to wonder if there needs to be a point to the work for something to be considered literature insofar as the author (or authors) must have a vision of where the work will lead and what they are trying to communicate for it to be literature. If I just put a bunch of random chapters together from several different pieces of literature, would the resulting work be a piece of literature? I don't know that I have the answer, but I believe that these questions have given way to even more intriguing dilemmas in determining what is literature.

Finally, I thought about what reading is in relation to the Wiki novel. Truthfully, I find it incredibly difficult to read any piece of literature online, and I grow impatient and begin to scroll through the work faster than I'm reading it. This brought up the tangibility of the printed word, in that it's harder for me to skip several chapters in a book that I'm reading than it is to skim down several chapters in a make believe Wiki novel. As the presence of literature on the internet grows, I believe it will lead to interesting questions on whether they nature of reading will change as well. Will we still dedicate the same time and attention to something that is displayed in front of us on a glowing computer monitor? In the case of A Million Penguins, I confess that my time and attention could have spent reading something more worthwhile.

Nonetheless, I did find A Million Penguins to be interesting, if only for the fact that it raises complicated questions about the nature of literature, authors, and reading in an increasingly media savvy world.

Saturday, March 1, 2008

Eliot, Modernism, and the Paradox

In my continuing internal debate about the merits of Formalist criticism, I came across an interesting article discussing the relationship between T.S. Eliot and Modernism. "T.S. Eliot and Modernity", written by Louis Menand, begins to assess the relationship between the Modernist movement and Eliot. Menand writes,

Eliot never courted the academy; he took the opportunity, on various occasions, of insulting it. But the modern academy, at a crucial moment in its history, made an icon of Eliot. And this suggests that the answer to the question of Eliot's success is likely to be found not simply in what he had to say but also in the institutional needs his writing was able to serve.Menand raises an interesting point. In our last several classes of Literary Criticism, we've discussed Eliot, his ideas, and his influence. And yet, in Menand's view at least, Eliot despised the institutions of higher learning. The paradoxical nature of Eliot is intriguing - Menand goes on to write that Modernism, as Eliot knew of it, was a reaction against the modern. And so the paradox continues. Or does it?

In Menand's view, romantic ideas still persisted in Eliot's culture of modernity, a situation which Eliot found deplorable. Certainly, Eliot's writing does seem to be reacting strongly against Emerson's Romanticism. Eliot focuses on literary technique over divine intervention, and form over content. And yet, there continues to be something in Eliot's writing that remains paradoxical, or even suspect.

Every writer has their own beliefs and experiences which invade their writing, no matter how much they might wish for their writing to be devoid of personal biography. For Eliot to argue otherwise is, in my opinion, nonsensical. Certainly, there may be overly sentimental or biographical poems which may not be worthy of study, yet it seems impossible that any writer, ever, can be completely unaffected by their personal experiences.

Ultimately, there seems to be some sort of impossible paradox in Eliot's writing. Menand writes that Eliot's criticism and writing were admittedly ad hoc in that they were writing criticism which applied to their own writing. For me, however, Eliot's criticism goes beyond simply ad hoc. While Eliot certainly offered valuable ideas for readers to consider while reading poetry, I ultimately find his writing to be to paradoxical to put much stock in.

Friday, February 29, 2008

The Affective Fallacy

Certainly, for the Formalist critics William K. Wimsatt, Jr., and Monroe C. Beardsley, the emotional response of the reader is never adequate ground for judging the meaning and value of a poetic work. However, I must confess that I often find myself judging the value of a poem based on my emotional reaction to the work. Many times, my emotional response is the ultimate indication of whether or not a poem is successful. I have, admittedly, found the criticism of the Formalists difficult to accept, their views often in stark contrast to my own.

To my understanding, the Formalists believe the reader's job has an obligation, in a way, to "fit" the poem, insofar is the reader has the responsibility to say that the one's immediate emotional reaction to a poem is not the meaning of the poem, or even an appropiate response to a poem. For Wimsatt and Beardsley, emotions have no grounding for judging the meaning of a poem. In contrast, I find myself naturally taking a much more impressionistic critical approach, a position that is in stark contrast with Formalism. It has been a difficult to ask to escape this point of view, even for a class period, and while reading Wimsatt and Beardsley, one thought continued to pop up. I just don't get it.

Poetry is, and always has been, an emotionally manipulative form of art for me. One of my favorite poems is "Funeral Blues" by W.H. Auden, which is a poem that has always stirred me into a contemplative, sorrowful state of mind. I love the poem because it does what I cannot, in that it perfectly articulates what it means to feel grief over a loss. I find the poem to be successful because it expresses feelings which I resonate with, feelings that cloud my judgment when trying to objectively decipher the value of the poem. However, I don't find fault with my belief in the success of the poem. On the contrary, I value the poem mostly because it provides me with a visceral emotional reaction upon my reading.

Ultimately, Wimsatt and Beardsley express an opinion on poetry that I simply don't find to be that compelling in light of my own experiences. Is the reader's emotional response adequate grounds for judging meaning and value? I must say, for me, the answer is always yes.

Tuesday, February 26, 2008

Authorial Intent

Saturday, February 23, 2008

Formalism

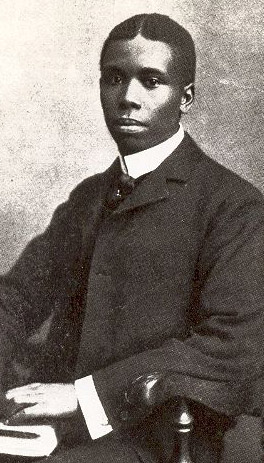

When we began to discuss Formalism in class on Thursday, we looked at the poem "We Wear the Mask." I was not aware of the poem before I encountered it in class, and upon my first reading of text, I immediately felt that I could resonate with the content of the poem. I thought the poem to be commenting on the state of society and the idea that we all have pain which we hide from the world. The poem seemed to speak about a universal suffering society endures with a smile, a theme that not only resonated with me, but with my fellow classmates as well.

When we learned the author of the poem was Paul Laurence Dunbar (right), an eminent African-American poet, for many of us the poem took on a deeper meaning. I immediately felt the significance of the poem change for me, from a superficial common suffering to a poem reflecting on the lives of black Americans. There was a disconnect of sorts, in that I felt that I couldn't understand the same pain that Dunbar, as an African-American growing up immediately after the Civil War, experienced during his lifetime.

Therein lies the foundations of Formalist criticism. Why should I feel a disconnect with the poem after learning of its author? Did I not feel the poem resonate with me upon my first reading, when the author and the history behind the poem was yet still unknown? This was a complex issue for me to consider. Throughout my time at Messiah, there has always been an emphasis on the author of a work, and how the historical setting and authorship of a work lends itself to the overall meaning of a text. I have pages upon pages filled in my English notebooks of biographical history, and many of my literature classes were organized by genre. I've taken Modern British Literature, Medieval Renaissance, and Early American Literature, among other lit classes. In each of these class we set the texts with which we engaged in a historical era, reflecting on the significance of time and author.

Now, after beginning to understand a bit of Formalism, I wonder how if these texts would have a different meaning for me had I not known its era, or author, and whether or not these elements ultimately change the significance of a work. Certainly there was a shift in my understanding of "We Wear the Mask", and I believe that at least some of the work I've encountered during my time as an English major would be altered had I been ignorant of its biography.

It will be interesting for me to consider different texts from a Formalist perspective, focusing on the content and form over other parts of a work. While I am not yet sure how much I agree with Formalism, I do believe that it will be beneficial for me to engage in literary works from a different perspective.

Friday, February 22, 2008

Acquiring Tradition

Throughout my four years as an English major, and even in the few times I've written on this blog, I have often written of my passion for reading. My belief in the power of reading is undeniable, for it is an act which not only enlightens my worldview, but also strengthens my own writing. Eliot's views on the necessity of reading serve not only as an intriguing bit of anti-Romantic criticism, but also, in my opinion, as an invaluable piece of advice for any burgeoning writer.

Eliot's views on tradition, however, are harder for me to discern. Undoubtedly, Eliot's use of the word "tradition" is complex, its appearance signalling a multitude of signficance. Certainly Eliot uses the word "tradition" to convey a sense of timelessness, with the past and the present coming together to form a new "tradition." In class, a quote from William Faulkner's famed novel Requiem for a Nun was brought up as a helpful way of discerning the meaning of Eliot's use of "tradition":

The past is never dead. It's not even past.

The idea that the past is never behind us, but instead is forever connected with our present lives, is an idea that is admittedly confusing. I tend to view things in such black and white that a complex theories such as Eliot's and Faulkner's are hard for me to digest.

As I continue to engage in Formalist criticism and begin to more fully understand Eliot's complex views, it will be interesting to see how my own views on the role of tradition will be altered.

Wednesday, February 20, 2008

Every Ray of Various Genius

Colleges, in like manner, have their indispensable office, -- to teach elements. But they can only highly serve us, when they aim not to drill, but to create; when they gather from far every ray of various genius to their hospitable halls, and, by the concentrated fires, set the hearts of their youth on flame. Thought and knowledge are natures in which apparatus and pretension avail nothing. Gowns, and pecuniary foundations, though of towns of gold, can never countervail the least sentence or syllable of wit. Forget this, and our American colleges will recede in their public importance, whilst they grow richer every year.

Saturday, February 16, 2008

A Theory of Romanticism

Peckham's statements on the seemingly non-existent theory of romanticism got me thinking - is there a theory of romanticism? Of course, our class and this blog are devoted to the discussion of various literary theories, with romanticism being our literary topic of the week, but can we actually articulate a theory of romanticism? Or, if we can articulate a particular theory, what would this theory look like?

In Peckham's view, we can and should define a literary theory of romanticism. He writes,

It must be able to get us inside individual works of literature, art, and thought: that is, to tell us not merely that the works are there, to enable us not merely to classify them, but to deliver up to us a key to individual works so that we can penetrate to the principles of their intellectual and aesthetic being.

It seems to be true that through the articulation of a definitive theory of romanticism, one may able to unlock what it means to be divinely inspired, or more essentially, what it means to define something as being a part of romanticism. After all, the romantic movement is undoubtedly influential still today. This is especially true of Messiah College. Our English department at Messiah shows an influence of romanticism in their mission statement, in which they proclaim the study of English to be important because, among other things, it fosters and develops the imagination.

Of course, these words mean nothing if we don't understand and articulate a theory of romanticism. Peckham begins to define a theory of romanticism by looking at the world as dynamically organic - always growing and changing, a world where something can be learned from nothing. In this world of ever-changing ideas and growth, the imagination is "radically creative."

Peckham seems to be on to something here. Percy Bysshe Shelley in particular articulated the power of poetry on deepening a more meaningful imagination. I've already mentioned Messiah College's belief that English and poetry are essential to a developed imagination. Peckham believes that the Romantics rose up into their unconscious imagination, not delved down. This, of course, is central to theory of transcendentalism.

Finally, Peckham articulates the central view on his theory of romanticism. Romanticism is that which rebels against the static, moving towards a world of "dynamic organicism." Romanticism is that which prizes, in Peckham's words, "change, imperfection, growth, diversity, the creative imagination, the unconscious."

While I don't know that I agree with all of Peckham's views - "dymanic organicism" being a particularly hard pill to swallow- he does seem to hit on some valuable ideas of romanticism. Certainly in our class readings we have seen the importance of values such as growth, imagination, and the unconscious. It seems to me that the Romantics were always striving to do something greater, to be something greater.

Of course, I don't know that I am able to define a theory of romanticism any better than Peckham's attempt. I can only hope that as I continue to engage in my studies of literary theory, my knowledge and understanding of the theories of various forms of literature will grow and deepen (as the Romantics would have wanted).

Friday, February 15, 2008

What is poetry?

Shelley's insight into the power of poetry is, in my mind, remarkable. Who can deny the power of a beautiful poem on the imagination? I defy anyone who can read Wordsworth or Keats, Byron or Browning, and not feel their imagination ripening with each stanza. The power of words on our hearts and minds is undeniable.Poetry enlarges the circumference of the imagination by replenshing it with thoughts of ever new delight, which have the phower of attracting and asimilating to their own nature all other thoughts, and which form new intervals and interstices whose void for ever craves fresh food. Poetry strengthens that faculty which is the organ of the moral nature of man, in the same manner as exercise strengthens a limb.

Poetry turns all things to loveliness; it exalts the beauty of that which is most beautiful, and it adds beauty to that which is most deformed: it marries exultation and horror, grief and pleasure, eternity and change; it subdues to union under its light yoke all irreconcilable things.

Through poetry's exultation of the beautiful, we are able to cope with our grief and pain, reconciled to the belief that though we may suffer, there is still enormous beauty in the world. In this way, Shelley's view on poetry poetry is much the same way that I view my Christian faith. While there are undeniable evils in the world, I am able to cope with these because my faith also provides me with emotions such as hope, love, forgiveness, and faith. Without these parts of living that are so wonderful, life would be overwhelmingly depressing. Similarly, a world without poetry, a world which is filled with, in Shelley's words, the "deformed", would be a world of horrors, without hope, or beauty, or imagination.

Wednesday, February 13, 2008

Emerson & Whitman

While reflecting on Romanticism and Transcendentalism after reading Emerson's "The Poet", my thoughts began to venture to another great Transcendentalist poet, Walt Whitman. In particular, I was struck by the great number of similarities I see existing between Emerson's "The Poet" and Whitman's "Song of Myself," with each work acting as an encouragement of sorts, urging the reader to rejoice in themselves, denying the artificial or the controlled.

One of the things I find to be most encouraging about "The Poet" is Emerson's sense that we all, each of us, have the ability to see the beauty that poets see and so beautifully interpret. I love the idea of the poet as as a representative for the common man, able to communicate with a transcendent world that most would simply find to be inaccessible. Emerson writes,

The breadth of the problem is great, for the poet is representative. He stands among partial men for the complete man, and apprises us not of his wealth, but of the common-wealth. The young man reveres men of genius, because, to speak truly, they are more himself than he is. They receive of the soul as he also receives, but they more.

Indeed, this sentiment is also echoed in Whitman's "Song of Myself" as Whitman tells the reader that while the poem is essentially a celebration of himself, he is also universalized. In the opening lines Whitman writes,

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

In proclaiming themselves to be representatives of the common man, a universalized poet if you will, both Whitman and Emerson seem to be exercising a healthy ego. They may see themselves as connected to the rest of us mere mortals, but Emerson did proclaim himself to be complete, and Whitman did name his poem "Song of Myself" not "Song of Ourselves." I don't begrudge them of this - in fact, the first time I read "Song of Myself" I celebrated with Walt Whitman, appreciating the banalities of life with a new passion. I love that both Whitman and Emerson reject the artificial, with Emerson declaring what art is not and Whitman rejoicing in, among other things, "the bustle of growing wheat."

Each time I finish reading a Romantic/Transcendentalist work, I am always inspired to reflect on the beauty in my own life. Reading Emerson or Whitman almost becomes a form of spirituality, inasmuch as I come away with a new appreciation for my God-given talents and blessings. With Whitman, I begin to recognize the beauty of the world, and with Emerson, I start to realize that I too can can touch this beauty.

Finally, I found this YouTube on Emerson that some may enjoy. Emerson lovers of the world, unite!