Friday, February 29, 2008

The Affective Fallacy

Certainly, for the Formalist critics William K. Wimsatt, Jr., and Monroe C. Beardsley, the emotional response of the reader is never adequate ground for judging the meaning and value of a poetic work. However, I must confess that I often find myself judging the value of a poem based on my emotional reaction to the work. Many times, my emotional response is the ultimate indication of whether or not a poem is successful. I have, admittedly, found the criticism of the Formalists difficult to accept, their views often in stark contrast to my own.

To my understanding, the Formalists believe the reader's job has an obligation, in a way, to "fit" the poem, insofar is the reader has the responsibility to say that the one's immediate emotional reaction to a poem is not the meaning of the poem, or even an appropiate response to a poem. For Wimsatt and Beardsley, emotions have no grounding for judging the meaning of a poem. In contrast, I find myself naturally taking a much more impressionistic critical approach, a position that is in stark contrast with Formalism. It has been a difficult to ask to escape this point of view, even for a class period, and while reading Wimsatt and Beardsley, one thought continued to pop up. I just don't get it.

Poetry is, and always has been, an emotionally manipulative form of art for me. One of my favorite poems is "Funeral Blues" by W.H. Auden, which is a poem that has always stirred me into a contemplative, sorrowful state of mind. I love the poem because it does what I cannot, in that it perfectly articulates what it means to feel grief over a loss. I find the poem to be successful because it expresses feelings which I resonate with, feelings that cloud my judgment when trying to objectively decipher the value of the poem. However, I don't find fault with my belief in the success of the poem. On the contrary, I value the poem mostly because it provides me with a visceral emotional reaction upon my reading.

Ultimately, Wimsatt and Beardsley express an opinion on poetry that I simply don't find to be that compelling in light of my own experiences. Is the reader's emotional response adequate grounds for judging meaning and value? I must say, for me, the answer is always yes.

Tuesday, February 26, 2008

Authorial Intent

Saturday, February 23, 2008

Formalism

When we began to discuss Formalism in class on Thursday, we looked at the poem "We Wear the Mask." I was not aware of the poem before I encountered it in class, and upon my first reading of text, I immediately felt that I could resonate with the content of the poem. I thought the poem to be commenting on the state of society and the idea that we all have pain which we hide from the world. The poem seemed to speak about a universal suffering society endures with a smile, a theme that not only resonated with me, but with my fellow classmates as well.

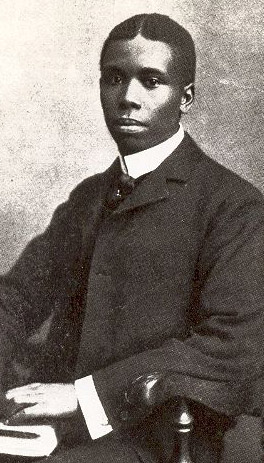

When we learned the author of the poem was Paul Laurence Dunbar (right), an eminent African-American poet, for many of us the poem took on a deeper meaning. I immediately felt the significance of the poem change for me, from a superficial common suffering to a poem reflecting on the lives of black Americans. There was a disconnect of sorts, in that I felt that I couldn't understand the same pain that Dunbar, as an African-American growing up immediately after the Civil War, experienced during his lifetime.

Therein lies the foundations of Formalist criticism. Why should I feel a disconnect with the poem after learning of its author? Did I not feel the poem resonate with me upon my first reading, when the author and the history behind the poem was yet still unknown? This was a complex issue for me to consider. Throughout my time at Messiah, there has always been an emphasis on the author of a work, and how the historical setting and authorship of a work lends itself to the overall meaning of a text. I have pages upon pages filled in my English notebooks of biographical history, and many of my literature classes were organized by genre. I've taken Modern British Literature, Medieval Renaissance, and Early American Literature, among other lit classes. In each of these class we set the texts with which we engaged in a historical era, reflecting on the significance of time and author.

Now, after beginning to understand a bit of Formalism, I wonder how if these texts would have a different meaning for me had I not known its era, or author, and whether or not these elements ultimately change the significance of a work. Certainly there was a shift in my understanding of "We Wear the Mask", and I believe that at least some of the work I've encountered during my time as an English major would be altered had I been ignorant of its biography.

It will be interesting for me to consider different texts from a Formalist perspective, focusing on the content and form over other parts of a work. While I am not yet sure how much I agree with Formalism, I do believe that it will be beneficial for me to engage in literary works from a different perspective.

Friday, February 22, 2008

Acquiring Tradition

Throughout my four years as an English major, and even in the few times I've written on this blog, I have often written of my passion for reading. My belief in the power of reading is undeniable, for it is an act which not only enlightens my worldview, but also strengthens my own writing. Eliot's views on the necessity of reading serve not only as an intriguing bit of anti-Romantic criticism, but also, in my opinion, as an invaluable piece of advice for any burgeoning writer.

Eliot's views on tradition, however, are harder for me to discern. Undoubtedly, Eliot's use of the word "tradition" is complex, its appearance signalling a multitude of signficance. Certainly Eliot uses the word "tradition" to convey a sense of timelessness, with the past and the present coming together to form a new "tradition." In class, a quote from William Faulkner's famed novel Requiem for a Nun was brought up as a helpful way of discerning the meaning of Eliot's use of "tradition":

The past is never dead. It's not even past.

The idea that the past is never behind us, but instead is forever connected with our present lives, is an idea that is admittedly confusing. I tend to view things in such black and white that a complex theories such as Eliot's and Faulkner's are hard for me to digest.

As I continue to engage in Formalist criticism and begin to more fully understand Eliot's complex views, it will be interesting to see how my own views on the role of tradition will be altered.

Wednesday, February 20, 2008

Every Ray of Various Genius

Colleges, in like manner, have their indispensable office, -- to teach elements. But they can only highly serve us, when they aim not to drill, but to create; when they gather from far every ray of various genius to their hospitable halls, and, by the concentrated fires, set the hearts of their youth on flame. Thought and knowledge are natures in which apparatus and pretension avail nothing. Gowns, and pecuniary foundations, though of towns of gold, can never countervail the least sentence or syllable of wit. Forget this, and our American colleges will recede in their public importance, whilst they grow richer every year.

Saturday, February 16, 2008

A Theory of Romanticism

Peckham's statements on the seemingly non-existent theory of romanticism got me thinking - is there a theory of romanticism? Of course, our class and this blog are devoted to the discussion of various literary theories, with romanticism being our literary topic of the week, but can we actually articulate a theory of romanticism? Or, if we can articulate a particular theory, what would this theory look like?

In Peckham's view, we can and should define a literary theory of romanticism. He writes,

It must be able to get us inside individual works of literature, art, and thought: that is, to tell us not merely that the works are there, to enable us not merely to classify them, but to deliver up to us a key to individual works so that we can penetrate to the principles of their intellectual and aesthetic being.

It seems to be true that through the articulation of a definitive theory of romanticism, one may able to unlock what it means to be divinely inspired, or more essentially, what it means to define something as being a part of romanticism. After all, the romantic movement is undoubtedly influential still today. This is especially true of Messiah College. Our English department at Messiah shows an influence of romanticism in their mission statement, in which they proclaim the study of English to be important because, among other things, it fosters and develops the imagination.

Of course, these words mean nothing if we don't understand and articulate a theory of romanticism. Peckham begins to define a theory of romanticism by looking at the world as dynamically organic - always growing and changing, a world where something can be learned from nothing. In this world of ever-changing ideas and growth, the imagination is "radically creative."

Peckham seems to be on to something here. Percy Bysshe Shelley in particular articulated the power of poetry on deepening a more meaningful imagination. I've already mentioned Messiah College's belief that English and poetry are essential to a developed imagination. Peckham believes that the Romantics rose up into their unconscious imagination, not delved down. This, of course, is central to theory of transcendentalism.

Finally, Peckham articulates the central view on his theory of romanticism. Romanticism is that which rebels against the static, moving towards a world of "dynamic organicism." Romanticism is that which prizes, in Peckham's words, "change, imperfection, growth, diversity, the creative imagination, the unconscious."

While I don't know that I agree with all of Peckham's views - "dymanic organicism" being a particularly hard pill to swallow- he does seem to hit on some valuable ideas of romanticism. Certainly in our class readings we have seen the importance of values such as growth, imagination, and the unconscious. It seems to me that the Romantics were always striving to do something greater, to be something greater.

Of course, I don't know that I am able to define a theory of romanticism any better than Peckham's attempt. I can only hope that as I continue to engage in my studies of literary theory, my knowledge and understanding of the theories of various forms of literature will grow and deepen (as the Romantics would have wanted).

Friday, February 15, 2008

What is poetry?

Shelley's insight into the power of poetry is, in my mind, remarkable. Who can deny the power of a beautiful poem on the imagination? I defy anyone who can read Wordsworth or Keats, Byron or Browning, and not feel their imagination ripening with each stanza. The power of words on our hearts and minds is undeniable.Poetry enlarges the circumference of the imagination by replenshing it with thoughts of ever new delight, which have the phower of attracting and asimilating to their own nature all other thoughts, and which form new intervals and interstices whose void for ever craves fresh food. Poetry strengthens that faculty which is the organ of the moral nature of man, in the same manner as exercise strengthens a limb.

Poetry turns all things to loveliness; it exalts the beauty of that which is most beautiful, and it adds beauty to that which is most deformed: it marries exultation and horror, grief and pleasure, eternity and change; it subdues to union under its light yoke all irreconcilable things.

Through poetry's exultation of the beautiful, we are able to cope with our grief and pain, reconciled to the belief that though we may suffer, there is still enormous beauty in the world. In this way, Shelley's view on poetry poetry is much the same way that I view my Christian faith. While there are undeniable evils in the world, I am able to cope with these because my faith also provides me with emotions such as hope, love, forgiveness, and faith. Without these parts of living that are so wonderful, life would be overwhelmingly depressing. Similarly, a world without poetry, a world which is filled with, in Shelley's words, the "deformed", would be a world of horrors, without hope, or beauty, or imagination.

Wednesday, February 13, 2008

Emerson & Whitman

While reflecting on Romanticism and Transcendentalism after reading Emerson's "The Poet", my thoughts began to venture to another great Transcendentalist poet, Walt Whitman. In particular, I was struck by the great number of similarities I see existing between Emerson's "The Poet" and Whitman's "Song of Myself," with each work acting as an encouragement of sorts, urging the reader to rejoice in themselves, denying the artificial or the controlled.

One of the things I find to be most encouraging about "The Poet" is Emerson's sense that we all, each of us, have the ability to see the beauty that poets see and so beautifully interpret. I love the idea of the poet as as a representative for the common man, able to communicate with a transcendent world that most would simply find to be inaccessible. Emerson writes,

The breadth of the problem is great, for the poet is representative. He stands among partial men for the complete man, and apprises us not of his wealth, but of the common-wealth. The young man reveres men of genius, because, to speak truly, they are more himself than he is. They receive of the soul as he also receives, but they more.

Indeed, this sentiment is also echoed in Whitman's "Song of Myself" as Whitman tells the reader that while the poem is essentially a celebration of himself, he is also universalized. In the opening lines Whitman writes,

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

In proclaiming themselves to be representatives of the common man, a universalized poet if you will, both Whitman and Emerson seem to be exercising a healthy ego. They may see themselves as connected to the rest of us mere mortals, but Emerson did proclaim himself to be complete, and Whitman did name his poem "Song of Myself" not "Song of Ourselves." I don't begrudge them of this - in fact, the first time I read "Song of Myself" I celebrated with Walt Whitman, appreciating the banalities of life with a new passion. I love that both Whitman and Emerson reject the artificial, with Emerson declaring what art is not and Whitman rejoicing in, among other things, "the bustle of growing wheat."

Each time I finish reading a Romantic/Transcendentalist work, I am always inspired to reflect on the beauty in my own life. Reading Emerson or Whitman almost becomes a form of spirituality, inasmuch as I come away with a new appreciation for my God-given talents and blessings. With Whitman, I begin to recognize the beauty of the world, and with Emerson, I start to realize that I too can can touch this beauty.

Finally, I found this YouTube on Emerson that some may enjoy. Emerson lovers of the world, unite!